Punch Perfect: The Science That Makes Boxing Knockouts Possible

Boxing fans always marvel at the spectacle of a knockout. A single punch can end a fight instantly, but it’s not magic – it’s physics and biology at work. Generating KO power starts from the ground up: fighters push hard with their legs and twist their hips, sending force up through the core and into the fist. In other words, if you throw more mass quickly, you create a bigger impulse on your opponent. This impulse-momentum relationship (basically F=ma) explains why heavyweights often hit the hardest. Even a smaller boxer like Gervonta “Tank” Davis can score KOs by moving very fast – he packs his whole body into the punch and uses timing to compensate for size.

How Knockout Power is Generated

Punching power comes from the whole body working together. Boxers learn to drive off the back foot and shift weight into their strike. Key elements include:

- Leg Drive & Weight Transfer: The feet push hard against the ground (ground-reaction force), sending energy up through the legs and hips. Firing the back leg into a punch (like a batter drives off the mound) helps accelerate the fist. Mike Tyson famously exploded from his legs and hips into hooks and uppercuts, giving his punches enormous power.

- Hip & Torso Rotation: Twisting the hips and torso acts like a coiled spring. As the boxer unwinds (rotates), torque builds and amplifies the force. For straights (crosses), the body translates forward; for hooks and uppercuts, the body rotates around its axis. In fact, hooks use a pivot on the lead or rear foot and a powerful torso turn to whip the fist in an arc.

- Core Stability and Snap: A tight midsection bridges legs and arms. The core transfers energy efficiently from the lower body to the upper body. At impact, the boxer “locks out” the arm (often called the snap or effective mass) so the punch isn’t wasted in bending. All these factors (mass, velocity, and technique) add up to KO power.

For example, scientific studies show elite boxers generate more punch force by engaging their back leg and hips for a straight cross, rather than just throwing the arm. Hooks and uppercuts rely even more on hip rotation in advanced fighters. In short, nearly all the power in a knockout punch comes from the legs and waist – the fist is just the delivery system.

Anatomy of a Knockout: The Chin and Jaw

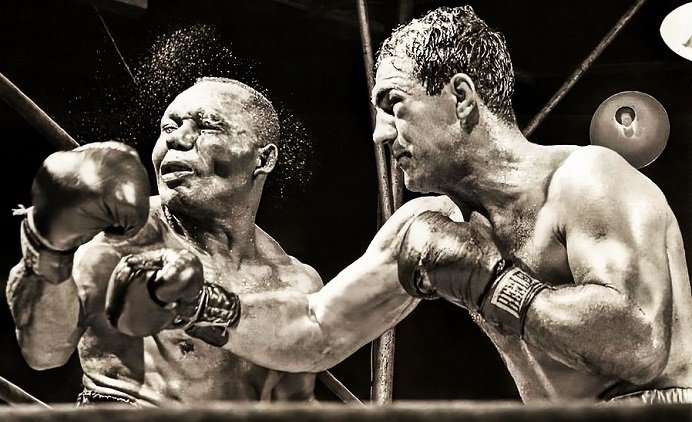

Not all punches cause knockouts – it matters where you hit. The chin and jaw are prime targets because a blow there makes the head snap violently. When the jaw is hit, the brain sloshes and smacks the inside of the skull, causing a brief shut-down (unconsciousness). A clean shot to the chin sends the brain into a “rattling frenzy,” making a quick knockout most likely.

In contrast, punches to the forehead or top of the head do relatively little to unsettle the brain. The sides of the head (including the temple and jaw hinge) are especially dangerous – these spots allow the skull to rotate sharply and break the opponent’s equilibrium. (This is why fighters are taught to tuck their chin and keep it behind the lead arm as a shield) In summary, the “sweet spot” for a KO is the point of the chin or the jaw’s side, where a punch induces maximum head rotation and brain impact.

Punch Types: Hook vs. Uppercut vs. Straight

Different punches deliver power in different ways:

- Straight punches (jab/cross): A cross (rear-hand straight) is like thrusting the whole body forward. The boxer drives off the back leg and shifts weight into a linear punch. This alignment lets maximum mass travel into the target. For a fast, flying straight (like Muhammad Ali’s famous “float like a butterfly, sting like a bee” left crosses), most power is generated by extending the legs and torso forward rather than just pulling the arm back. The jab (lead hand straight) is quicker but comes from the front leg; it’s often used to set up heavier shots.

- Hooks: A hook travels in a semicircular arc from the side. To throw a hook, the boxer pivots on the lead foot (for a lead hook) or rear foot (for a rear hook), shifting weight to that foot. The hips and shoulders whip around, bringing the fist in horizontally. Because hooks use a wide, swinging motion, they often pack extra torque and can connect to the side of the head where KOs happen. The rear hook in particular engages the entire body’s rotation and is “particularly effective for generating knockout power”.

- Uppercuts: An uppercut comes from below, usually at close range. The boxer bends the knees and explodes upward, using a combination of leg drive and core rotation. This rising punch can crack an opponent under the chin, and in tight inside-fighting an uppercut’s compact path makes it dangerous (think Joe Frazier’s famous left uppercuts on Muhammad Ali). Unlike straights, uppercuts rely on vertical leg power plus the hip twist – they can feel like the entire body is “throwing” the punch upward.

Each punch, when well-executed, can be a knockout punch under the right conditions. The physics (mass, speed, impulse) are the same, but the path of the fist and angle of impact differ. A straight cross hits with a large percentage of the body’s mass behind it, while a hook or uppercut can sneak around defense and hit the temple or jaw from an unexpected angle.

Legendary Knockouts and What Made Them Effective

Many famous KOs illustrate these principles. For example:

- Mike Tyson (1980s): Tyson was relatively short for a heavyweight, but he used his low stance and explosive legs to unleash hooks and uppercuts from close range. In his 91-second demolition of Michael Spinks, Tyson slipped inside, drove off his legs, and fired a compact hook/uppercut combo into Spinks’s chin. This “peek-a-boo” style maximized his leg and hip power for devastating effect.

- Deontay Wilder (2010s): Wilder’s one-punch KO rate is legendary (40 KOs in 44 wins). Standing 6’7″ with long arms, he often throws a looping right (an overhand or hook) that uses his full-body torque. Wilder’s punches land with extraordinary momentum – he famously knocked out Gerald Washington and Alexander Povetkin with single blows. His rear hook/overhand relies on the same full-body pivot described above, and his tall frame adds extra momentum (mass) to each strike.

- Gervonta “Tank” Davis (2020s): Davis (a 135-pound boxer) mixes speed and precision to get KOs. From a southpaw stance he often jabs to the body and head, then unleashes a heavy lead left. He even knocked out Rolando Romero and Isaac Cruz with sharp lefts. Notably, Davis lands hard left hooks to the body that drop opponents’ guards – these body blows set up head shots for knockouts. His high KO ratio comes from carefully timed, high-impact shots delivered at angles few can predict.

Other historic examples include legends like George Foreman (raw power drives) and lighter punchers like Joe Calzaghe (speed plus placement). In every case, the knockout punch combined mass, speed, and precision. Whether it was Tyson’s explosive hook or Wilder’s lethal right hand, the common thread is full-body coordination and hitting that vulnerable spot on the chin or temple.

Training for Punching Power

Fighters do targeted training to boost their KO power. Key methods include:

- Strength & Conditioning: Squats, deadlifts, lunges and power cleans build the leg and hip strength needed for explosive driving power. A strong core is crucial for transferring force, so exercises like medicine-ball throws or rotational lifts help “punch through” with the torso. Trainers often say “train your legs, punch with your legs” – developing leg and hip strength translates into harder punches.

- Plyometrics & Speed: Exercises like jump squats, box jumps or speed-bag work improve explosiveness. The faster a boxer can move his body mass, the more powerful the punch. Speed drills (shadow boxing with weights, resistance band punches) train the neuromuscular system to fire quickly. Studies and coaches agree that explosiveness is just as important as raw strength in maximizing punch force.

- Technique Drills: All that strength must be applied correctly. Fighters spend hours on the heavy bag and focus mitts, practicing the exact hip rotation and weight transfer for each punch. Drilling combinations at full speed ingrains the timing of hip twist and shoulder rotation. A properly timed hook/uppercut with perfect form uses more power than a wild swing.

- Neck and Body Conditioning: A stable, strong neck can slightly reduce knockout likelihood (by slowing head snap). Some fighters do neck bridges or resistance exercises. Core workouts (planks, medicine-ball slams) also improve the whole-body transfer.

- Footwork and Timing: Good foot positioning can make a punch land with full force. For instance, pivoting under a punch helps a fighter throw counter-hooks with more hip rotation. Drills that simulate slipping and counterpunching help fighters harness that stored energy at the right moment.

In practice, boxing training cycles combine skill work with gym strength sessions. Many strength coaches use data: for example, Boxing Science measured that boxers (and especially heavyweights) can generate forces several times their body weight in milliseconds. So they tailor workouts to improve explosive strength (fast, heavy movements) rather than just max lifts. The result is more KO power in the ring.

Conclusion

The knockout punch is a perfect storm of physics and physiology. It relies on delivering maximum momentum to the right target (usually the chin or jaw) with perfect timing. Champions like Tyson, Wilder, and Davis achieved their KOs not by “magic” but by mastering technique – loading up their legs and hips, rotating explosively, and striking when their opponent’s head is most vulnerable. By training strength, speed, and technique together, any boxer can improve his “punching technique” and KO power. So next time you see a lights-out knockout, you’ll know: it was science, technique, and timing all coming together in one moment.

Post Comment